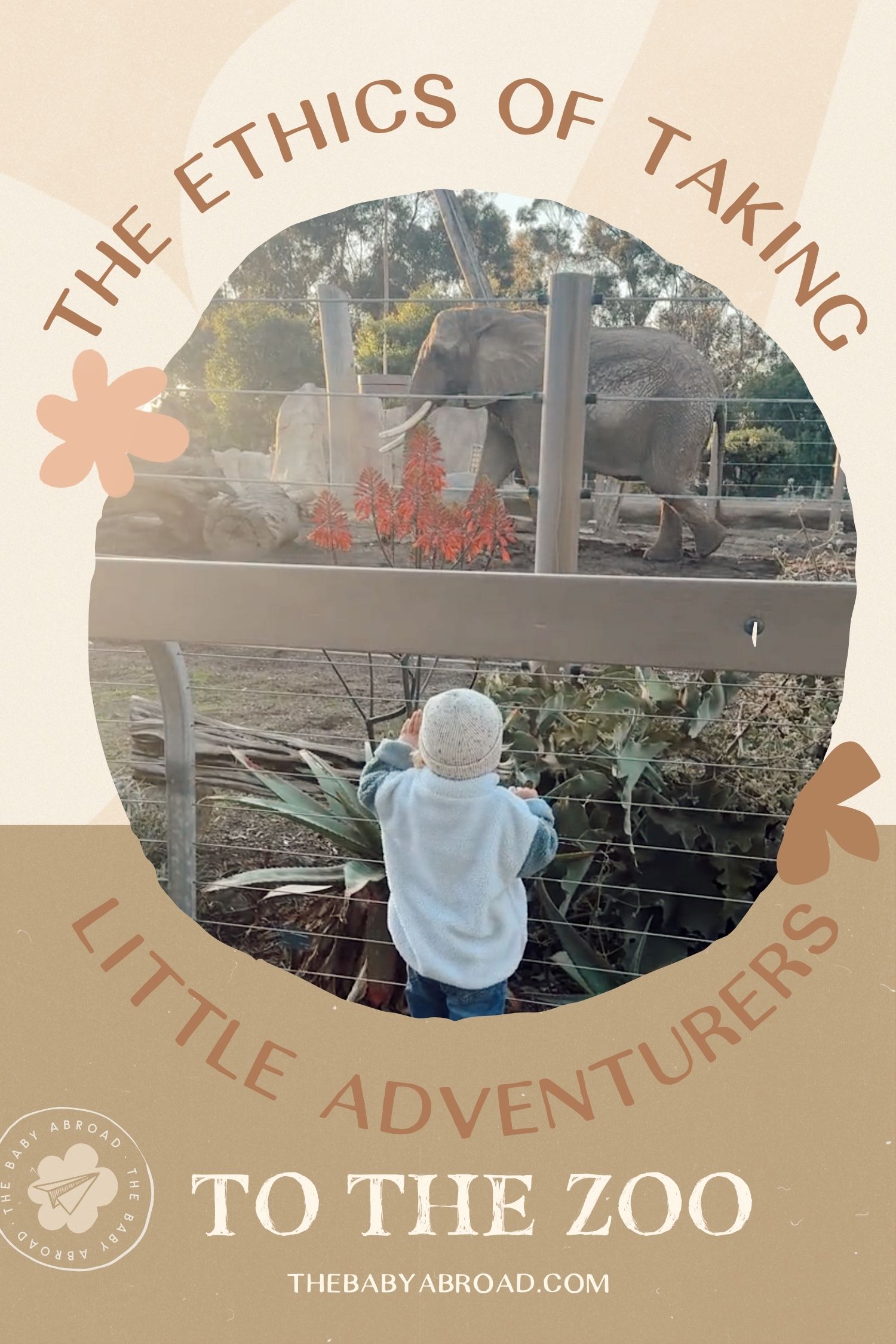

Let’s dive into a thought-provoking topic close to my heart –

the ethics of taking your kiddos to the zoo.

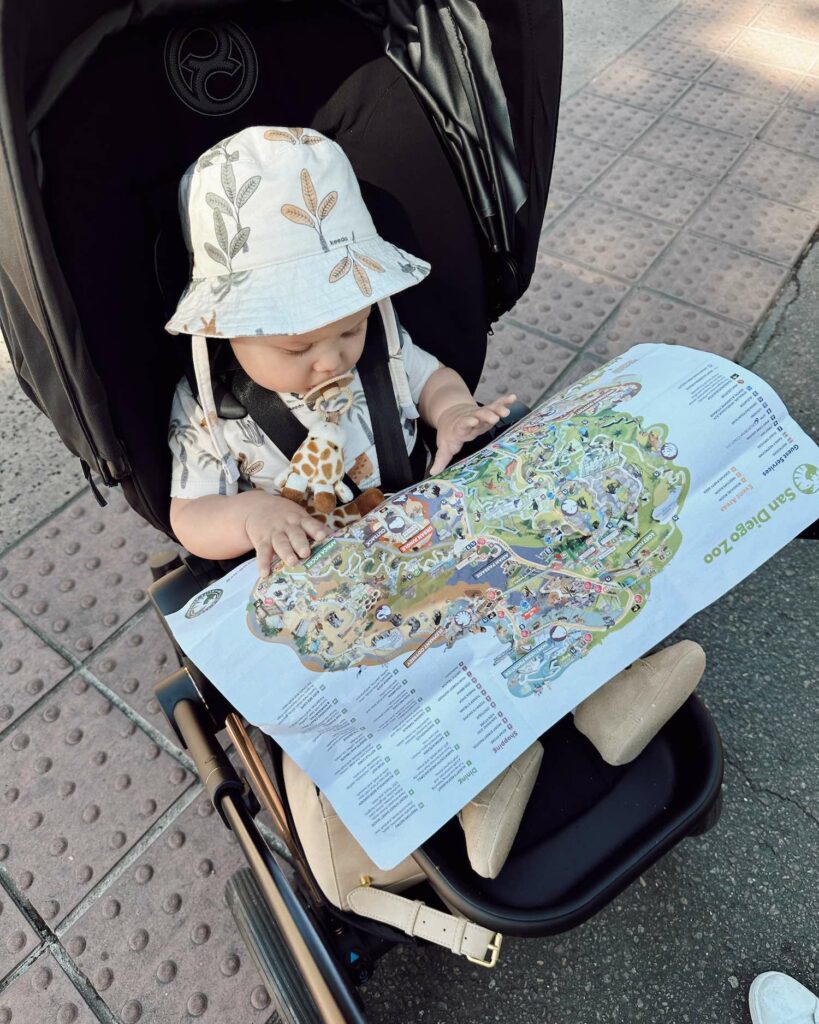

As parents, we’re always on the lookout for magical experiences that ignite the curiosity in our little explorers. The zoo seems like the perfect place, right?

Or maybe, like me, you start spiraling down a dark path, questioning all of your life choices and endlessly second-guessing whether zoos are places for education and conservation OR a lifetime of hell for wild animals.

The topic is complex and nuanced, so we’ve asked two experts to weigh in on some of the biggest questions and concerns about the ethics of visiting zoos, aquariums, and wildlife sanctuaries.

Let’s chat about the ethical jungle we might be stepping into when visiting a zoo!

Meet the experts

Anna Veronika

An animal lover from a young age, Anna spent many years working with animals – including six years working at a zoo. She studied biology at her university and went on to study for her masters in wild animal biology, where much of her studies focused on zoo animal welfare. While she doesn’t work in the wildlife field today, she remains passionate about wildlife conservation and advocacy.

Robin Glazer

Robin has volunteered, interned, and worked in wildlife facilities like zoos, museums, and rescues. Her grad studies focused on resource allocation for keepers, organizations, and animals, bridging gaps in zoo-keeping. Transitioning to advocacy, she champions environmental causes at a legislative level. She supports positive environmental policies in Delaware and regional clean water coalitions, bridging communities and governments.

Let’s start with your hot take on zoos, sanctuaries, and aquariums before we dig into the BIG questions and concerns readers shared.

I want to start off by saying no zookeeper wants to care for animals in captivity. We would all prefer to see them thriving in their native habitats, but it isn’t always possible. Climate change, deforestation, and human-wildlife conflict are just some threats to wild animals that live in the wild. With that said, it is an immense privilege to go to work every day.

Zoos, aquariums, museums, and sanctuaries all play an integral part in the conservation. I recognize that the word “zoo” has a complex–often cruel–history and connotation, but like many other aspects of the human experience, it has evolved over time. Where zoos started as collections of curious specimens from around the world (including different people – yes, people were “kept” in zoos! A very tragic part of history), they are now centers of conservation, preservation, and science.

While I am overall positive towards (accredited) zoos, I do definitely question keeping wild animals in captivity from an ethical perspective and there are many forms of interaction with animals that I personally wouldn’t participate in.

People have a lot of different opinions about keeping wild animals in captivity; in the end, it’s about doing what you feel comfortable doing with the information you have. It’s also okay if that evolves over time – I’ve absolutely visited places in the past that I wouldn’t know based on what I know today.

How can we verify that a zoo is good or bad? While traveling, I’ve noticed some countries have very bad zoos.

Just like restaurants, schools, and hair salons, there are many different ways to define good and bad. For starters, zoos in the United States and Canada are generally accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA), the Zoological Association of America (ZAA), and/or Canada’s Accredited Zoos and Aquariums (CAZA). There are similar organizations around the world so that you can do an internet search for “country” zoos and aquariums.

To be an accredited zoo, there is an adherence to (very highly set) minimum standards. Accreditation is one of many metrics of a good zoo or aquarium. Generally, if you see a facility that has achieved multiple metrics (or lacks them), it is very telling of the quality.

Remember that many sanctuaries don’t allow guests, as they don’t have the staffing and/or capacity to accommodate the public. Zoos, aquariums, and other places that are open to the public have income from tickets, programming, and shops – money that goes directly to the operating budget for the animals.

Make sure you are only visiting accredited zoos. Types of accreditation vary from country to country, but in the US, zoos should have an AZA accreditation, and in Europe, look out for the EAZA accreditation. Any zoo with accreditation should be a good zoo to visit.

If you want to read up on what zoos need to do to get these accreditations, you can visit the AZA website and the EAZA website.

How can we know the accreditation/reputable status of a zoo?

Check out the zoo’s website and social media, accrediting agencies, or health agencies. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), and other governmental agencies also play integral roles in the animals a facility can have and their health and environmental needs.

Accredited zoos should highlight their accreditation on their website (often in the website footer). You can also look out for how they present themselves online. They should, for example, have information on animal welfare and enrichment programs.

London Zoo is a good example of this; if you visit their website, you will see they have a section dedicated to their conservation work.

You can also ask for this information on-site; any reputable zoo should be able to provide you with information on their accreditation and animal welfare efforts.

Museums, sanctuaries, and rescues often have accrediting bodies:

Where can you visit some of the best zoos, aquariums, or animal sanctuaries?

These locations have been researched for their safest practices towards animals and even awarded for some of their conversation efforts:

Best Zoos in the USA:

- Maryland Zoo in Baltimore (Maryland)

- Wildlife Conservation Society’s four zoos and one aquarium (New York)

- San Diego Zoo and Wildlife Park (California)

- Denver Zoo (Colorado)

- Smithsonian National Zoological Park (Washington, D.C.)

- Georgia Aquarium (Georgia)

- Lincoln Park Zoo (Illinois)

Best International Zoos:

- The Belize Zoo (Belize)

- Cheetah Conservation Fund (Namibia)

- Two Oceans Aquarium (South Africa)

- London Zoo (England)

- Lone Pine Koala Sanctuary (Australia)

- Taronga Zoo (Australia)

Is supporting a “good” zoo also supporting “bad” zoos?

Interest in zoos in general will mean that there will always be the possibility that people will attempt to run bad zoos. However, the more people are aware of how to avoid bad zoos and do so, the fewer visitors they will get, which hopefully force them to close down.

I agree with Anna on this one. Educating people about how to tell the difference is the best way to shut down bad ones. Don’t give bad ones your patronage or support. Visiting good facilities directly funds their animal care, conservation, and educational programs.

How do we contribute to better zoos, aquariums, and conservation efforts?

Always research before visiting any place that keeps animals in captivity, and only put your money towards places you feel confident are legitimate and doing good work.

Visit them, participate in their programs, and share your experiences. There is a wonderful quote by Baba Dium, a Senegalese forest engineer:

“In the end, we will conserve only what we love; we will love only what we understand, and we will understand only what we are taught.”

You may be surprised how many people of all ages have never seen a cow in person, much less a bison. Having the experience of getting “up close and personal” with wildlife encourages care and compassion that can’t be learned solely from the internet.

What are the red flags or big “don’ts” for places that claim to be orphanages or sanctuaries? Things like camel rides and animal encounters around the world. How do we determine which are ethical and which aren’t?

This is a tough one, and often it’s hard to determine if these places are responsibly run. Make sure to look closely at how they present themselves online; they should have a big focus on animal welfare on their website and social content and clearly describe how they achieve this. Look out for accreditations and collaborations with legitimate organizations.

If you are concerned, speak to the staff over the phone or in person, and don’t take part in any animal encounter if you don’t feel confident about having the animals’ best interest at heart.

On-site, you can also check if the animals look healthy to you and whether their environment is clean.

Visit their website, ask friends and family, and check social media. What do you see and hear?

- Do they separate babies from parents who would otherwise be in a social structure when not medically necessary? (note: yes, there can be very good reasons to hand-raise an animal, but it is always a last resort)

- Are they making money from things like cub petting or primates wearing clothing?

- Are the animals chained and/or inappropriately housed in unsanitary or poor conditions?

- Are there obvious signs of injury or illness without explanation (i.e. signage, interpreters, or keepers answering questions)?

- Are the animals forced to be on display, lacking choice and control over where they can rest, move, or hide? (note: it can be very challenging, if not impossible, for guests to see what spaces the animal has access to – on and off exhibit)

If any of these are answered yes, ask many more questions before considering a visit. If the response seems shady or counterintuitive, it’s a red flag.

Some resources to consider:

Robin says to recognize the five freedoms:

It is also important to remember that different cultures have different standards and norms for animal care. A place called a “zoo” looks a lot different, too – but that’s not necessarily bad. The important things can be summarized in the five freedoms:

- From thirst, hunger, and malnutrition, by providing ready access to fresh water and a diet to maintain full health and vigor…

- From discomfort and exposure…

- From pain, injury, and disease…

- From fear and distress…

- To express normal behavior.

Are places like SeaWorld really any better after the “Blackfish” documentary? Living in San Diego, I feel good about going to the zoo, but bad about SeaWorld. Can you explain the difference?

I have never worked for Seaworld, but based on my knowledge and professional experience, there are many issues with the documentary, including the veracity of the statements. With that in mind, it is important to question our husbandry methods and strive for improvement continually. This is why you may see many marine mammals switch from “shows” to behavior demonstrations. The animals have choice and control in participating and showing behaviors, not performing tricks.

Housing large marine mammals (whales, dolphins, sea lions), elephants, primates, big cats, etc., is always a contentious discussion. It is emotionally complicated – for people and the animals.

Regardless of your stance on marine mammals in human care (captivity), Sea World is among the world’s top conservation and rescue organizations. We may never agree on some things, but you cannot doubt Sea World’s conservation contributions.

Some resources to consider:

Honestly, I share your concerns. I personally don’t visit places that keep whales and dolphins in captivity. That doesn’t mean these places are inherently bad and I believe the people working with these animals have their best interests at heart; it’s just where I have personally decided to draw the line. Mainly this is because I don’t think that the enclosures these animals are kept in make for a happy life for them, so I can’t justify visiting them.

How are animals acquired for zoos?

Today, most animals are moved between zoos through cooperative breeding programs. The AZA has programs that track the genetics of individuals within a species and match them with others based on viability and location. Animals can go from state to state or even to other countries, depending on what genetic diversity is needed. There is no monetary exchange, and the animals are not bought and sold between good zoos. Depending on the species, it is natural for juveniles to disperse from their families, form coalitions or bachelor herds, or even push existing dominant individuals out of their desired territory. Zoos mimic this by moving individuals based on species-specific behavioral needs.

It’s not a quick or easy process – there are generally years of planning, hundreds (or more) of dollars spent on transportation, and countless hours of prep time by zoo staff at both the sending and receiving facility.

Some animals are still taken from the wild in very rare cases. If there is an impending event, such as disease or famine, it can be appropriate to remove animals from the wild.

Accredited zoos are generally part of a breeding program where they don’t acquire animals from the wild, but breed them either in the zoo itself or in collaboration with another zoo. Breeding animals are genetically tested to ensure they are fit to breed with each other and ensure that zoo animals worldwide have genetically healthy offspring. As Robin mentioned, there is a complex system in place that speaks to the work put in to ensure the health of zoo animals.

Do the big cats get let out to run? How do they determine the size of the enclosure for each animal?

Accredited zoos must have enclosures of a certain size, depending on the species. This should allow the animal to display behaviors they would in nature but might not be the behaviors we as humans associate with them.

It’s also important to note that big cats are lazy and don’t generally run for fun – they run to hunt and spend the rest of their time lazing around and looking for their next meal. Many zoos do, however, include simulated hunting in their enrichment programs, for example, when the animals are fed, so in most cases, they will have a chance to display this behavior in captivity.

Big cats are some of the “laziest” species I have worked with! It’s important not to anthropomorphize wildlife by giving them human attributes and characteristics, so “laziness” is a quick way of saying “energy efficient.” All felids, including your house cat, sleep upwards of 20 hours a day. Many are often more active at night, so some zoos (Cincinnati Zoo, for example) have night houses where the light cycle is reversed for the guest experience. You can see them when they’re most active, but they still get a 24-hour day/night light cycle.

At reputable zoos, animals are provided ample food and opportunities to express natural behaviors, like hunting, foraging, smelling, and seeing novel items. If a cheetah doesn’t have to hunt, it’s not going to run 60 mph for fun).

As Anna said, each species has requirements and standards for habitat size, including felines. What you see may also be a part of their living space, with separate yards and dens to move the animals to for safety, medical, birthing, or other purposes.

What are the life expectancies of animals in captivity vs those in the wild?

This is species-dependent, but most zoo animals live longer than their wild counterparts. As you can imagine, this is largely because predators will not attack them and won’t have trouble accessing food and water like they may experience in the wild.

On average, animals in human care live longer than in the wild. Veterinary advances have increased their life expectancies and survival rates, contributing to wildlife rehabilitation success. There was a flamingo-standing incident in southern Africa a few years ago that saw the response of the global zoo community; keepers flew in from around the world to raise orphaned chicks using zoo-developed methods. Wild animals would be far worse off without this extensive husbandry (care) and medical knowledge.

Some resources to consider:

What are your thoughts on those who feel like visiting zoos means they’re contributing to the imprisonment of wild animals?

If you feel that way even after reading up on the topic, that is totally valid, and maybe zoos are not for you.

I love talking to people about zoos’ importance and the value of their visit. Yes, you contribute by visiting, sharing, and supporting. However, if you choose not to support zoos for personal reasons, that’s okay too. What matters is that you are open to learning the facts, embracing something different than you expect, and having the ability to grow. If all you take away from this article by two professionals in the field is that not all zoos are bad and that good ones play a huge role in wildlife conservation, then my goal is accomplished.

Did you know…

Zoos are the third largest financial contributor to global conservation. There are 700 million visitors to zoological facilities and $330 million dollars spent on conservation worldwide!

Are there any studies on the mental well-being of animals in captivity? I’ve heard some animals are on anti-depressants. Is that true?

Absolutely, what many people don’t know is that there is so much scientific research that goes on at zoos. This is done to improve zoo animal welfare and understand how certain species behave in the wild.

With regards to anti-depressants, I haven’t come across this myself, but that obviously doesn’t mean it never happens. What I can say is that in my experience, zoo staff make every effort to ensure the well-being of their animals. Zoo standards have also changed significantly over the years, and we have much better knowledge today on how to keep animals in captivity happy and healthy.

Yes! I am not a veterinary professional, but I have observed the beneficial use of different prescribed drugs over the years. I believe there is better living through medicine (as someone who deals with anxiety and depression myself). Animals in human care are never prescribed medicine without extensive veterinary physicals and advanced knowledge of the species. Just like people, some animals may be affected by certain environmental or social factors, which as a last resort, may require medical intervention. HOWEVER (I write in big letters to catch your attention), this is the exception, NOT the rule. Before prescribing medicine, every step is taken to address behavioral concerns, including diet, habitat structure, social access, and every single other consideration.

I have also seen individuals move to other facilities that had a better setup for that animal. This is where zoological accrediting associations and networks benefit most – by working together to provide the best possible animal care.

Some resources to consider (if you want access to an article that is behind a paywall, try emailing the author or zoo they work at – sometimes they’ll send it to you!):

Opinion to weigh in on: If there weren’t zoos, people would make more effort to see them in nature.

I have had the immense privilege to study wildlife worldwide in undergraduate and graduate schools. However, it is not feasible financially and otherwise for everyone to do this. Even from a time perspective – would you sit on a plane for 30+ hours, then a car, then a boat, then hike to see an orangutan in the wild? That’s what it took for me to observe them in Malaysian Borneo. Back in the States, I can drive a few hours to the Smithsonian National Zoo in D.C. to bring those feelings of wonder back, much closer to home.

Possibly to some extent, but traveling to see many species in the wild is a privilege most people can’t afford, so seeing animals in zoos is often the only exposure to wildlife they will get.

Opinion to weigh in on: Zoos do not educate, empower, or inspire children to become conservationists. There are other (better) ways to learn about the natural world without holding animals captive for their lifetimes to do so.

Watching a child explain to their parents what an okapi is while standing in front of the animal is empowering. Kids absorb new information and love to share it. They read books, watch shows, and have experiences we often forget as adults. So when a child sees something in person that they have only seen as a cartoon or photograph, it takes their breath away. These experiences, formal or informal, are so valuable to engaging people with the wild world. Every day we are further disconnected from nature – it’s precious to experience it firsthand when you can.

I disagree with this; there is a huge educational component in any good zoo and staff are trained to educate and answer questions about the animals and their conservation.

Visiting zoos as a child greatly influenced me growing up and it was a part of why I ended up being so passionate about wildlife. Seeing animals in real life has a completely different effect than seeing them on a screen. For lack of a better word – it makes them feel more real instead of being these hypothetical creatures you see on TV.

Of course, seeing animals in their natural habitat is the best-case scenario, and there are definitely other ways to learn about the natural world. However, zoos still play an educational role and, in my experience, can inspire children to become conservationists in the future.

Opinion to weigh in on: While this is all true, it doesn’t mean zoos should exist. Please consider sharing the other perspective.

I’m ready for a world that is safe for all – humans and wildlife. But that isn’t the reality. Zoos will continue to exist, evolve, and provide for countless species. Zoos are often called an “ark” for the very point of preservation of insurance populations.

At the end of the day, whether you think zoos should exist at all is a personal opinion, and you can make an argument for both sides. I can absolutely see why someone would be ethically opposed to zoos, just like many people don’t eat animal products or keep pets.

I believe that well-run zoos play an important educational role for the general public and an increasingly important role in conservation efforts. Overall, they do a lot more good than bad. But I also respect that that will not be everyone’s opinion.

What are some final thoughts or details you want to share with readers that feel conflicted about zoos?

I think many people may not be aware of the role zoos play in conservation efforts. Many zoos focus heavily on protecting species in the wild and keeping animals that are already extinct in the wild.

Zoos also focus on keeping animals in conditions that mimic their natural habitat to raise animals that could be released in the wild to help support vulnerable wild populations.

So, while zoos serve as a fun day out for families, the money they raise is important in conservation efforts.

Zookeepers often get accused of being in it for the money. Let me assure you this is absolutely, firmly NOT the case. Keepers, on average, make minimum wage or slightly more, but tend to have undergraduate or advanced-level degrees. The profession is emotionally and physically demanding, ever-changing, and highly specialized. I sometimes joke that I speak countless animal “languages,” as reading behavior can tell you everything you want to know about an individual. I can tell gazelle apart from a distance, know the moment a macaw isn’t feeling well, and yes, I can tell you which animal pooped that (and if it’s healthy!). Keepers write scientific papers, monitor chemical balances in aquatic environments, and build enrichment that would keep even the most discerning animal busy for hours.

While I am no longer a zookeeper, there’s a saying, “once a keeper, always a keeper.” It was the most impactful ten years of my life and has shaped how I interact with the world. I now have a newborn daughter and I can’t wait to share my career with her and tell her she can be anything she dreams of when she grows up. Maybe she’ll see the end of zoos in a world where all animals are safe in the wild. Either way, she will know her mom did everything she could to contribute to wildlife conservation as a keeper and after.